The U.S. Congress mandates that the Federal Reserve seek to achieve maximum employment, stable prices and moderate long-term interest rates in the U.S. The Federal Reserve itself operationalizes this “stable price” goal by stating that 2% annual inflation is “price stability”. This has never made sense to me. If prices rise 2% a year for one’s working life, the compounding effect will result in the need of twice as many dollars in retirement to buy what one bought when they started working. In other words, prices will have doubled in one’s working life. This is not very “stable” to me.

Not only does the Federal Reserve have a strange way of defining price stability, it also prefers to measure prices with the quirky “personal consumption inflation deflator” (PCE deflator), as opposed to the more widely used and understood consumer price index (CPI). While the Fed can offer wonderful research suggesting that the PCE deflator is a better measure, it is important to understand that no one aside from the Fed uses this measure. The U.S. Treasury uses the CPI in indexing their Treasury Inflation protected securities. The Social Security Administration uses the CPI to determine cost of living adjustments, as do most labor contracts. (An additional minor deficiency with the PCE deflator is that the data generally is published with a two week longer lag than the CPI data.)

Now the Fed use of the PCE deflator to gauge inflation, as opposed to the consumer price index, might be a trivial matter if there were no systematic difference in the two measures, but there is a systematic difference. Over the last ten years, there has never been a case when the PCE deflator showed more inflation than the CPI measure. Indeed, the CPI measure shows annual inflation over the last ten years to be almost 0.4% higher than the PCE deflator. In other words, the 2% price stability goal translates to about a 2.4% rate of CPI inflation.

Most financial analysts have been lamenting the recent low rate of inflation rate in the U.S., since it has been less than the 2% goal of the Federal Reserve, apparently acquiescing to the Fed’s price stability goal definition. Indeed, at the last Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting in December, two FOMC members even voted against raising the target for the federal funds rate, the process of “normalizing” interest rates, which the F.O.M.C. started in December 2015, because inflation was less that the 2 percentage point goal of the Fed.

This opposition to further normalizing short-term interest rates today presumes a tight causal linkage in which increases in short-term interest rates will result in lower inflation. While this linkage appears on the surface to make sense to most, as economists constantly preach its validity, there is little empirical support for it in recent data. U.S. inflation is much more volatile than the linkage suggests and there is little in the data of late to suggest slowing inflation as the FOMC has raised the target of the federal funds rate.

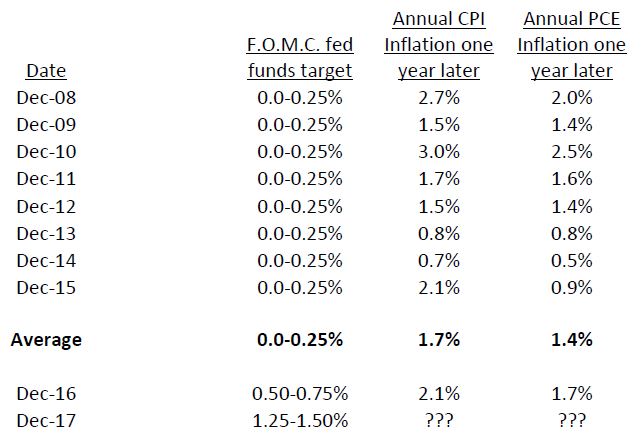

The table below presents the U.S. recent experience, linking the target of the federal funds rate with both the personal consumption and Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation rate one year later, to allow for a lagged impact of monetary policy. The top part of the table details the behavior of the two variables from 2008 to 2015. This period is selected specifically as the FOMC targeted the federal funds rate to be between 0% and 0.25% uniformly over this period. Since the target of the federal funds rate did not change, those that believe there is a tight link between monetary policy and inflation would believe that inflation itself should have been constant over this period.

Yet, the record shows that consumer price inflation on an annual basis was highly variable ranging from a high annual rate of 3.0% to a low of 0.7%, and PCE inflation varying between a low of 0.5% and a high of 2.5%. The evidence clearly suggests that something aside from the F.O.M.C.’s targeting of the federal funds rate, shapes the U.S. inflation rate. As such, the evidence suggests that the FOMC has very limited ability to control annual inflation in the U.S. with any great precision and the wisdom of letting the pattern of inflation dictate key monetary policy decisions appears suspect.

Those that argue the F.O.M.C. should not now increase the target of the federal funds rate also suggest that an increase in the target federal funds rate will lead to a lower inflation rate following the FOMC higher targets for the federal funds rate.

Interestingly, the evidence is not consistent with this prediction. As the FOMC has increased the target of the federal funds rate beginning in December 2015 and continuing in 2016, CPI inflation remains steady at 2.1%, while PCE inflation actually increased from 0.9% to the most recent 1.7%. While we won’t know the full effects of the 2017 increases for a number of months, the increasing price of oil and the falling value of the dollar are not suggestive of falling inflation rates.

In summary, there appears nothing in U.S. inflation behavior over the last ten years to warrant pausing the normalization of interest rates. Moreover, those individuals saving for eventual retirement should understand that the Fed’s definition of price stability is going to require them to have many more dollars available for consumption than what they might surmise from today’s purchasing power.

Implications for Community Banks

- The Fed’s concern about inflation is backward looking, and comes with a significant lag. (We just got news about the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation for December 2017.)

- The ultra-low interest rates set by the Fed since the financial crisis did little to stimulate economic activity and cause significant inflation. (In part, this is because depositors and other savers have been harmed by inflation, which has averaged close to 1.8%, causing a loss in purchasing power.)

- To the extent that ultra-low interest rates have done little to stimulate the economy, the converse is likely to be true; meaning that higher interest rates are unlikely to slow economic activity and rising inflation. (Depositors are going to feel much better when they can earn more than the inflation rate.)

- While the Fed started increasing short-term interest rates in December 2015, the current target for these rates remains below the Fed target for inflation. As such, monetary policy should not be viewed as currently “tight”.

- The Fed continues to try and provide guidance as to what it expects regarding future monetary policy. Recently, the Fed indicated that it expects to raise the target of the federal funds rate three more times this year, along with outlining a plan to gradually shrink its portfolio of long-term Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities.

- The guidance of the Fed should be viewed skeptically. There is much more interest rate risk today than observed over the last ten years. President Trump still needs to fill the majority of open Board of Governor positions, so the guidance provided by the Fed showed not be viewed the same as in the past. Moreover, the just passed tax reform act has good potential to further stimulate economic activity.

- To the extent that the Fed and other central banks have been significant buyers of longer-term fixed income instruments in recent years, the slope of the yield curve is likely to have less predictive power regarding future economic activity than we observed in the past when they never invested in such instruments.

by Scott Hein, President, Hein Consulting